120 Students Is Not a Bubble: What to expect when schools reopen in BC

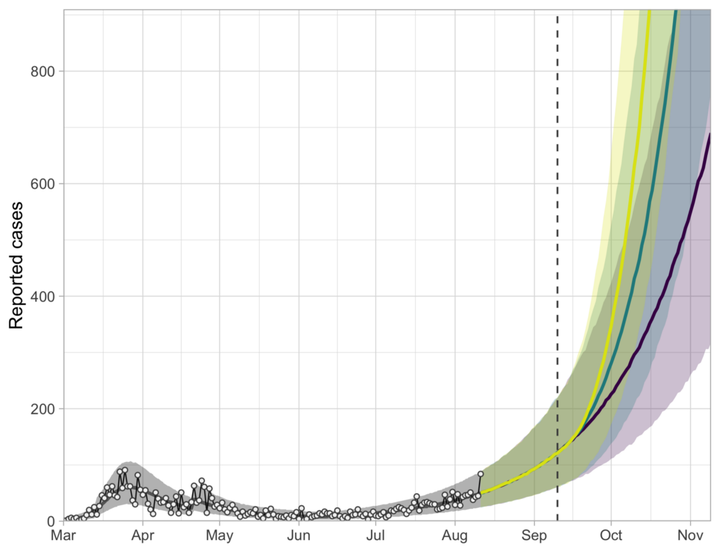

Bottom line is growth if we keep everything the same. Green and yellow lines are predictions for 10% and 20% more social contact among those who are distancing. Image credit: Sean Anderson

Bottom line is growth if we keep everything the same. Green and yellow lines are predictions for 10% and 20% more social contact among those who are distancing. Image credit: Sean Anderson

Currently things appear to be returning to normal in British Columbia. While in other parts of North America the pandemic rages, here, although cases are growing, the number remains small. Schools in BC were closed abruptly in March in response to COVID-19, but were then reopened in June without leading to disaster. The pandemic has appeared to be under control for most of the summer. With this background, the BC Government announced the reopening of schools for September. This decision involved weighing the social, educational, economic and health costs imposed by school closures against the risks of increased virus transmission.

We cannot tell anyone what is the correct way to weigh the costs and benefits of reopening schools, but we can use our group’s methods to give an idea of what to expect in September, both terms of both what happens to the students and their families, and the effect this will have on the pandemic on the whole.

The first point to make is that, despite appearances, we have entered a period of exponential growth in the number of COVID-19 cases in BC, with most of the cases being in the Lower Mainland. Our models forecast that unless we change what we are doing, this trend will continue, even if schools remain closed. We have relaxed social distancing too much already. It is counterintuitive that cases can be very low, as they were in June, but we had still relaxed too much, but that is the unfortunate logic of exponential growth. So what can we expect this fall?

For starters, how prevalent will COVID-19 be in September? In many areas of BC, hopefully it will still be very low. Using the modelling framework we developed for BC we forecast the prevalence by Sept 11, 2020 in BC to be between 1500 and 4000 cases, and by far the majority of these will be in the Vancouver Coastal Health and the Fraser Health regions, which have a combined population of about 2.85M. We can probably assume that the prevalence in school-age children is lower than the general prevalence because to date, children and teenagers haven’t had much exposure. And younger children may not be as likely to get infected. But the average high school has 1000–2000 students. Even if the prevalence in high school age students is 40% lower than prevalence overall, this gives about 1 in 2500 students infected already when schools reopen in the lower mainland. So the probability of any given student returning to school with COVID-19 is very low. This sounds great.

But what’s the probability that a school, with 1000 students or even 2000, has at least one student entering who is infectious? Well, hopefully over half of those who are infectious have symptoms and stay home, but the others will likely not know that they are ill, either because they haven’t had symptoms yet, or they won’t develop symptoms, or their symptoms are mild. The chance that a school with 1500 students has at least one entering who is infectious is 20–30%. That’s a large number of high schools in the VCH and FH region that are at serious risk of an outbreak, right away. In other regions, schools may be able to reopen for considerable time before cases get introduced, but those introductions are very hard to predict.

How large do we expect outbreaks to be if they do occur? What happens when school opens in September and an infected student attends? For high schools, without any preventative measures, our model predicts that a single asymptomatic student could infect between 10 and 25 other students in a single week. Then, before they know they are ill, those new cases could infect many other students, family members, teachers and other contacts. This could lead to outbreaks in the dozens to hundreds. We can’t be more precise than that because we don’t know the exact transmission rate in a particular high school environment or how soon the outbreak would be detected. Face masks and social distancing will make the numbers lower, as will students staying home if they feel sick (for those who get symptoms). But two lessons remain despite the uncertainty: the number of new infections will not be small, and bubble sizes of 120 (for high schools) and 60 (for elementary schools) will not make much of a dent.

But it appears that schools will reopen in BC in September, and we have to do everything we can to minimize outbreaks, and to prevent those outbreaks from spreading.

As schools have reopened in other parts of the world a picture of how to do it with relative safety is emerging. Places where school reopenings have been successful have had low prevalence of COVID-19 in the general population, and taken steps to keep it low. And measures were taken to prevent outbreaks in schools.

In BC schools were briefly reopened in June with no apparent ill effects. But our experience then is not a good model for reopening in September. For one thing, only elementary schools were opened, not high schools. For another, prevalence and community transmission were both very low, and lower than they will be in September in the Lower Mainland. And finally, class sizes were kept deliberately smaller than they will be now — students only attended one or two days a week and many stayed home altogether.

We need to do two things to make reopening as safe as possible.

- Reduce prevalence as much as possible in areas where there is community transmission by increasing social distancing measures. High risk, nonessential indoor activities need to be stopped. This will give us the leeway we need to reopen schools without leading to an explosive number of new cases. Many regions in BC can probably already reopen safely but in the Lower Mainland we need to get transmission under control.

- Structure schools to minimize and contain transmission within them. The most effective way to do this is with social bubbles, where the total number of other students each student has close contact with is kept small.

The BC government’s plan implements social bubbles with what they call Learning Groups. Learning groups will have up to 120 students in high schools and 60 in elementary schools. At first glance, these bubbles appear to be too large to be effective. But some of the suggestions for structuring instruction in the fall are more reassuring.

For example, for elementary schools, suppose the class size is 20 students. If we could guarantee that students only ever interacted with other students from that class, that would limit any outbreak to only 20 students, at least in the first set of infections (but family members and other close contacts could still be impacted). If we then say that students from two separate classes can freely and frequently mingle, we have just doubled the potential size of the initial outbreak to 40. But if instead, following the suggestion that “two classes that work together on shared projects” are only together for an hour a week, then that may be a short enough time that the risk of spread from one group to another is acceptable. Likewise, having just “up to three primary classes that go outside together on a regular basis” may work at containing outbreaks just because the improved ventilation of the outdoors makes transmission risk low.

Another lesson from our models is that preventative measures such as masks are most effective (in giving the most benefit per hour of use) when meeting new people for short periods of time. The discomfort of using a mask may be too much to expect of elementary school children for 30 hours a week of school. But if they only interact with students in another class for one hour a week, then there may be a big payoff to them wearing masks for that time.

We are sure of very little of what will happen when schools reopen in September, except that COVID-19 will still be with us. How it turns out — whether we have the success stories of countries like Denmark, Austria, or Singapore, or the many outbreaks of countries like Israel and the United States — — depends very much on how seriously we take steps to keep transmission and prevalence low, both inside and outside of schools.