High-transmission variants in Canada

What happens if a high-transmission variant becomes established, and is transmitted in the general community in Canada?

Here we illustrate the kind of reported case trajectory that we may see if a higher-transmission variant, such as the B.1.1.7 variant that has been rising dramatically in frequency in the UK, becomes established in Canada. Volz et al estimate that B.1.1.7 has a substantial transmission advantage - a 40-80% increase in the reproduction number, for example. An increase like that in the transmission rate is worse than a higher severity or mortality rate, because so many more people can get infected.

In most of Canada we have been able to control COVID-19 – at least, the variant(s) we have today – albeit with strong distancing measures (stay-at-home orders in Ontario, curfews and other rules in Quebec, restrictions on socializing with anyone outside your household - these are all familiar). But a variant with a 40+% increase in transmission rate (or similar increase in R) likely would not be contained with measures we have in place today.

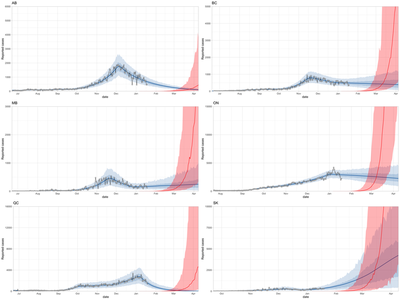

What would it look like if a variant with a 40% higher transmission rate got established here, under the current COVID-19 controls? We modelled this by adding growth of a new higher-transmission variant like B.1.1.7 to our regular covidseir model fits for Canada’s six provinces with substantial COVID-19 cases. The underlying model is described here (with further details below).

These are the results:

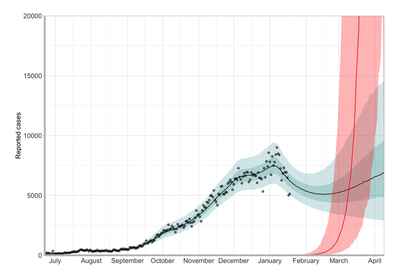

And here is the compiled Canada-wide version:

What does it mean?

The punch line is that failure to prevent or contain this now spells disaster in March. While we don’t see much impact for ~6 weeks, when it comes it comes steeply, with a doubling time of 1-2 weeks, compared to doubling times like 30-40 days recently in provinces like Ontario. Exponential growth is fast - when you’re halfway to the maximum capacity you can tolerate (in hospitalization, ICU, contact tracing capacity, or wherever the bottlenecks are), you only have one doubling time left. But it might have taken 8 doubling times to get to halfway. Methods

Here’s how the modelling works. We first use covidseir to fit the reported case trajectory for each province (separately). The covidseir model is a compartmental SEIR model that has two populations: those who are able and willing to participate in distancing (most of the population), and those who are not (for work or other reasons). When distancers do go out and have contact with others, they are less likely to contact other distancers (because they’re at home). The fitting is done in RStan, and the process estimates several parameters, including the underlying basic reproduction number (from the initial rise in March 2020) and the strength of distancing – in terms of the fraction f of the regular contact rate, among distancers. Lower fractions mean stronger distancing measures (or people following measures more fully).

We then project forward under the current estimates. We also model a strain like B.1.1.7 with a higher transmission rate - affecting both sub-populations, though the “distancers” still have a reduced contact rate. While we have made a good effort to fit the data, and the model accounts for some complexity (delayed and noisy reporting, pre-symptomatic transmission, distancing and changing measures over time, etc), this is a simple illustration and there are some limitations. Here are the caveats.

- The time of introduction of the new variant is the same in all the provinces – random, uniform in Jan 5 - Jan 25, 2021. This isn’t the time of introduction, but the time that community transmission becomes established.

- Currently, we are not able to detect whether each reported case is a variant type (B.1.1.7 or otherwise); we do some whole-genome sequencing and some qPCR testing that can detect B.1.1.7 via the S gene dropout, but it is very possible that there are a number (50? 100?) B.1.1.7 cases circulating that we don’t know about. If it were established earlier or later than January, shift the red curves earlier or later to imagine what the model would look like.

- In this modelling, the control measures currently in place continue indefinitely. This is not realistic, but serves to illustrate the impact of a higher-transmission variant even if we keep doing the stringent things we are doing today.

- Places like AB and MB get a double benefit - their current measures impact both variants, delaying the rise of the high-transmission variant. This does not necessarily contain B.1.1.7 (or any similarly high-transmission type)

- We have modelled a mean 40% increase in the transmission rate, compared to the COVID-19 circulating in Canada today

- Unfortunately the models are not linked - we have used the approximation that few Canadians have had COVID-19, so there is little immunity. The two variants are not experiencing much competition for hosts. If the new variant rises to high levels in this modelling, it does not suppress the ‘regular’ COVID-19 as it would if competition began to take place.

- The new variant’s trajectory does not reflect a build-up of immunity due vaccination. However, current vaccination strategies are not targeting transmission and we have limited natural immunity, so in the time frame of now to March, this is not an unrealistic assumption.

So what can we do?

We should take steps to prevent introductions of new variants into Canada: tighten rules on travel, define essential travel and stop non-essential travel. We should step up quarantine and isolation of travellers. We should improve detection, using tests that can detect B.1.1.7 (qPCR and whole genome sequencing) and other variants (mainly whole genome sequencing) – though B.1.1.7 is the one for which we have strong indications that it has higher transmission. But we must also be willing to act to curtail the spread of high-transmission variants - B.1.1.7 at the moment - in Canada.

If and when we find out that COVID-19 vaccines can impact transmission – and we think it is likely that they will – we could use vaccination as one of the tools in the transmission toolkit, for example by vaccinating truckers who need to cross the Canada/US border.

There have been a few detected B.1.1.7 cases already in Canada, and so far we hope that community spread has not yet been established. But we should be considering reducing travel within Canada, not just from outside it, because we may still need to prevent spread of B.1.1.7 between Canadian jurisdictions. And we should consider screening domestic travellers for B.1.1.7 if we can.

There may be time still to head off introductions and community transmission until many more of us are vaccinated. But that is months away, and right now, vaccination is not going to impact transmission in the 6-8 week time frame.

The Covid Strategic Choices group has a petition on this topic - see here for more details.